Chile’s Safe Class Law: Violence In Public Schools And The “Regulation” Of School Life

In 2008 UNICEF published the study “School life, an indispensable component of the right to education”, inquiring about internal regulations in educational establishments in the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, Chile. The results are surprising, for example, they showed that more than 50% of the regulations did not comply with the legal order in effect, that is, they transgressed or omitted rights, in particular regarding disciplinary matters. It was also noted that the regulations were reduced to a series of rules oriented only to disciplinary issues, which did not look at the community as a whole, nor the relationships, nor the responsibilities of all levels in the construction of reality. In addition, community participation was not validated in the vast majority of them. Finally, the study recommended not using the regulations to rule life in schools, at least not as they were then.

In 2011, after a media campaign against bullying in schools (for months we saw all kinds of cases in the morning news), the Law on School Violence was promulgated. It points out in its article f) that each establishment “must have an internal regulation that rules the relations between the establishment and the different actors of the school community” (Law 20.536, 2011). It adds that these regulations “must incorporate prevention policies, pedagogical measures, action protocols and several conducts that constitute a lack of good school life, graduating them from lesser or greater severity.” It also adds that “(…) disciplinary measures will be established according to such behaviors, which may vary from a pedagogical measure until the cancellation of the school’s registration”. (Law, 20.536, 2011) The law, proposed to deal with bullying and potential aggression against teachers, validates the regulations as a tool to rule behaviors at school.

Large numbers of students expelled

Something that isn’t said in any law but is also instituted, in some cases, is the possibility to expel or cancel the enrolment of a child from public education. In fact, it sets a “gradual procedure and with a ‘fair procedure’, which must be established in the regulations” (Law 20,536, 2011). In 2011, according to complaints received by the Network of Lawyers for the Defense of Student Rights (RADDE), by its Spanish acronym), about 11,000 young people were expelled or had their enrolment canceled throughout the national territory (Vejar, 2012). According to complaints received by the Superintendency of Education only, about 500 students have been expelled from their establishments every year. The First National Report on School Expulsion of the Superintendence of Education indicates that, according to reports, in 2015 there were 1.3 students expelled per day (of these, 27% lost their school year) (Superintendence, 2016). This hides a dark scenario. What happens to all of those who do not report, are relocated or simply cancel their registration? In some Liceos (schools), after a mobilisation period, dozens of students have been expelled, relocated or canceled with the excuse of normalising the school life.

Negative long-term impact

It should be noted that the interruption of the educational trajectory has serious consequences for young people’s life plan. We know that in Chile there are already almost 80,000 children and young people outside the school system. We know that a large percentage of those who see their educational trajectory interrupted end up dropping out of school and fall into “educational exclusion.”

With the educational trajectory interrupted, the child leaves school and the school abandons them. They lose their emotional relationships, institutional support networks, everyday space, and personal and family rituals. As such, their identities, personal projections and life projects are seriously affected (Terigi, 2004). And so we ask: How can relocation, cancellation of tuition or expulsion be considered educational measures?

The Safe Class Law aggravates the situation

This Safe Class law gives the “principal the power to suspend, as a precautionary measure and for the duration of the sanctioning procedure, the students and members of the school community who, in an educational establishment, have incurred in any of the serious or very serious offenses established, according to the internal regulations of each establishment, and that carry as a sanction ”(…) the expulsion or cancellation of the enrolment, or seriously affect the school life, in accordance with the provisions of this law.” It also establishes a period of just 5 days to appeal such decision and, if not settled, the student is permanently expelled. The State endorses it, even saying that “it will ensure the relocation of the sanctioned student to establishments that have professionals who provide psychosocial support” (Law 21.128, 2019).

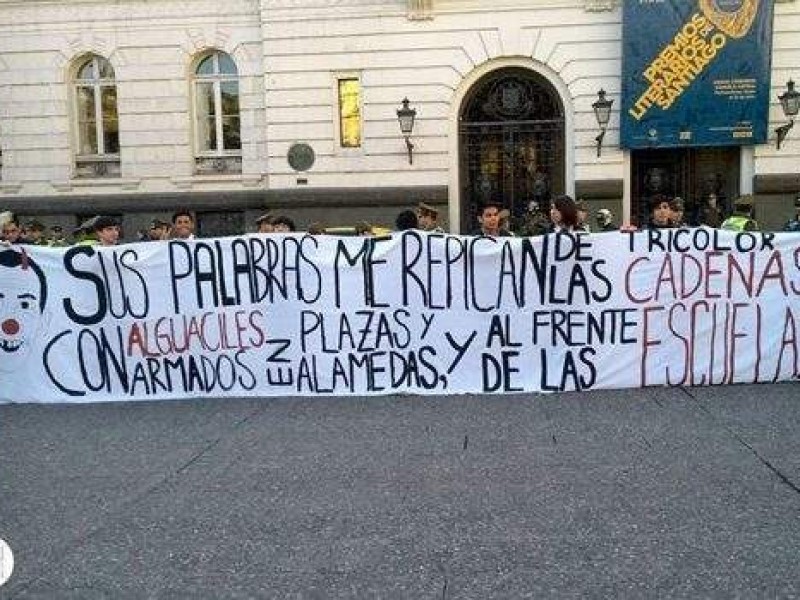

Once the law was approved by the Congress, the problem has intensified, particularly in the commune of Santiago. Mobilisations are held in some high schools, discontent grows due to the crisis in public education, regulations are tightened, some students are criminalised and the number of expelled students increases.

We must deal with the cause, not the symptom

While the crisis generates violence, we must deal with the cause, not the symptom. Is the solution getting away from the rotten apple? That is eugenics, a terrible approach to apply in schools.

We educators must, at least, reflect on psychosocial harm inflicted to children, families and communities after this wave of expulsions. School life can’t be reduced to a regulation. What are the school councils, the psychosocial teams, and the pedagogical experience of teachers good for? Or better yet, what happens to the underlying problems? No school that has seen a significant improvement in its educational conditions (infrastructure, improvement of working conditions, increased participation, etc.) has experienced such problems. Clearly, the dialogue has broken down in some public high schools, and expelling students is not the best way to restore it.

Author: Foro por el Derecho a la Educación Pública

References

Becerra, L. C. (2008). La convivencia escolar, componente indispensable del derecho a la educación: estudio de reglamentos escolares. Unicef.

Superintendencia de Educación (2016) Informe expulsiones

Terigi Flavia, (2009). Las trayectorias escolares. Del problema individual al desafío de las políticas públicas.

- de Chile (2011) Ley 20.536 Violencia Escolar

- de Chile (2019) Ley 21.128 Aula Segura

UNESCO-OPECH (2018). Hacia un mundo sin muros: educación para la ciudadanía mundial en el ODS 4 – Agenda E2030

Véjar, P. (2012). Informe RADDE: Criminalización de la movilización estudiantil en Chile en el año 2011. Santiago: Asociación Chilena pro Naciones Unidas/Foro por el Derecho a la Educación. Retrieved January, 14, 2017.

Abraham Magendzo (2018) Reflexión en torno al proyecto de ley «Aula Segura»